The London Magazine

The current ‘Hajj’ exhibition at the British Museum has been praised by Brian Sewell as ‘an exhibition of profound cultural importance’ and criticized by Mehdi Hasan as a ‘whitewash’. It is both, as it happens, though the former finally outweighs the latter.

The whitewash accusation refers to the fact that there is no mention of the on-going destruction by Saudi Arabia, whose Abdul Aziz Public Library is the British Museum’s partner in hosting the exhibition, of important Muslim historical and cultural sites. Wahhabism, the puritanical form of Islam that dominates in Saudi Arabia, permits the destruction of such sites because they are believed to encourage idolatry. Indeed, the Saud family Wahhabi tribes destroyed many sites as they advanced into the Hijaz during the nineteenth century. It is estimated that the vast majority of Mecca’s ancient buildings have been destroyed in recent decades. Nor does the visitor to the exhibition learn that Mecca has been filled with ugly shopping malls, and Mohammed’s birthplace marked for demolition to make way for a new Saudi royal palace.

This is clearly a matter that needs to be addressed by any British cultural institution working with Saudi Arabia. Nevertheless, the importance of this exhibition should not be in doubt. ‘Whitewash’ fully acknowledged – and, after all, many objects in the British Museum were acquired through ‘whitewashed’ colonial exploitation – this exhibition nevertheless provides a fascinating journey towards an understanding of Hajj. The pilgrimage (one of the many early meanings of hajj is ‘visit’) is undertaken by an astounding three million Muslims every year, who travel to Mecca from all over the world. It is, as one display panel tells us, ‘both a collective undertaking and a deeply personal experience’.

Hajj is one of the five pillars of Islam, required of every Muslim man or woman who is in good health and can afford to travel, and the only one that non-Muslims are forbidden from performing. Indeed, non-Muslims are not even allowed to enter Mecca, and as a result, Hajj has remained mysterious and seemingly impenetrable to westerners.

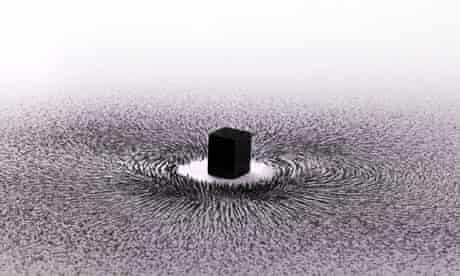

The exhibition takes the visitor on an enlightening journey through several stages that represent the stages of pilgrimage, from preparation, through to Hajj itself and its rituals, and finally to homecoming and memories of Hajj. It is a text-heavy exhibition, with lots of panels and descriptions. They are worth the time and effort, however, and there are also many beautiful artefacts of historical and cultural significance. There are, to name but some of these, centuries-old prayer books, rare Qurans, illustrated manuscripts and maps, a Hijaz commemorative watch, Qibla indicators and compasses to work out the direction of the Kaaba, an ornate nineteenth-century Mahmal or ceremonial palanquin, postcards, pilgrimage tickets, old and contemporary photographs, tiles, textiles, embroidered panels for the Kaaba, flasks for the water of the holy Zamzam spring, pilgrims’ manuals from all historical periods, pebbles from Muzdalifa, kitsch modern souvenirs, and thoughtful contemporary artistic representations of Hajj, including Ahmed Mater’s Magnetism.

The focus on the journey forms a good part of the first half of the exhibition, and informs us about the difficulty of travelling to Mecca before air travel. The journey was long and arduous, with people crossing deserts and oceans, by camel, horse or on foot, often vulnerable to disease and robbery. Because Hajj takes place at a certain time of the year, people travelled in convoys and gathered at one of three main points: Kufa in Iraq, Damascus in Syria and Cairo in Egypt. The exhibition charts the different African, Arabian, Ottoman, Indian Ocean and British routes throughout history.

We learn about extraordinary historical figures such as the pious Queen Zubayda (765?-831 AD), wife of the Caliph Harun al Rashid, who went on Hajj five times in the eighth to ninth centuries, and ordered the construction of water wells and stations for tired, thirsty pilgrims. Then there is the journey in the fourteenth century from Timbuktu across the Sahara of Mansa Musa, the King of Mali, which took many months. He was so wealthy that he travelled with an enormous retinue of servants and a hundred camels carrying gold, which he distributed generously along his way. We learn about Evliya Çelebi, the famous Ottoman travel writer, who rode his horse to Mecca in 1672. We discover that Thomas Cook was the official travel agent for Hajj from 1886 to 1893 from colonial India, but gave it up because it wasn’t profitable enough, and that a rich but frail person in the eighteenth century could send someone to perform Hajj on his or her behalf and receive a proxy Hajj certificate.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is a thirteenth-century book, the Maqamat al Hariri. Maqamat (meaning “assemblies”) was a genre in Arabic literature consisting of rhymed prose narrated by a merchant Al Harith and featuring the roguish character Abu Zayd. The book on display is illustrated by the Iraqi painter, Yahya al-Wasiti and the beautiful, vibrant pictures of Abu Zayd on Hajj depict the lively movement of a raucous caravan of pilgrims being harangued by Abu Zayd about the meaning of Hajj.

We can also see the book that made Sir Richard Burton famous. It relates his own experience of Hajj in 1853, when he disguised himself as an Afghan doctor and Sufi dervish and joined an Egyptian Hajj caravan. The earliest English account of Hajj is on show. It is by Joseph Pitts, a sailor who was captured by Algerian pirates, sold at auction in Algiers and forcibly converted to Islam. His third owner treated him well and took him on Hajj in 1680. There are also letters and a prayer book belonging to the first British woman to perform Hajj. At the age of 65, Lady Evelyn Cobbold made the journey to Mecca in the 1930s, with the permission of King Abdel Aziz.

Several displays and a short film explain the rituals of Hajj itself and Umra (the secondary pilgrimage) and the different stages of Hajj that take a few days to complete. Pilgrims first change into the white ihram garments in one of five locations surrounding Mecca and say the Talbiya prayer that announces their arrival.

Tawaf is the ritual of circling the black, cube-shaped Kaaba seven times (and touching the black stone on its eastern corner if possible). Pilgrims then commemorate the search for water by Abraham’s exiled second wife, Hagar, and son, Ismail, by walking their three-kilometre route and sipping water from the Zamzam spring. They continue to the overnight camp at Mina, east of Mecca, and the day-long vigil on the mount in the Arafat plain where Mohammad gave his farewell sermon. At dusk they go to the rocky Muzdalifa plain and collect pebbles for the stoning of the pillars; this re-enacts the story of Abraham throwing stones to caste out evil. Eid al Adha (the festival of sacrifice) follows, in which an animal is sacrifice and the meat distributed to the poor. A final stoning of the pillars and farewell circling of the Kaaba completes Hajj.

‘[A]s a believing Muslim’, Mehdi Hasan ‘felt a tingle of excitement’ as he ‘spotted the rare, eighth-century Quran on display’. There is little doubt, however, that any visitor who immerses him or herself in the absorbing experience of the exhibition will share that tingle of excitement, whether Hindu, atheist or simply interested in art, books, culture, history or the Middle East.

The exhibition succeeds in providing an understanding and an appreciation of a centuries-old pilgrimage that involves millions of people from around the world. It informs both Muslims and non-Muslims about Hajj and its history, and allows non-Muslims to participate in Hajj in a cultural, intellectual and perhaps even spiritually moving way. If true cosmopolitanism entails an imaginative act of sympathy with others, then this exhibition is an excellent instance of London’s contemporary cosmopolitanism.