The Male Nude at the Wallace Collection has a slightly more sensational title than it warrants. With its hint of role reversal – today’s spectator is used to the female nude in Western art but generally less aware of representations of the male – it initially seems to fill a gap in the same way as the contemporaneous exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, Masculin/ Masculin: L’Homme nu dans l’art de 1800 à nos jours.

The Orsay’s is an enormous crowd-puller that has gathered examples of male nudes in drawings, paintings, sculpture and photography in Western art since 1800. It is impressive in scale and diversity, but the way in which it brings together disparate works whose principal or only unifying thread is the representation of the male nude is at times tenuous. The further one proceeds from room to room, each of which groups together certain works thematically – the classical ideal, the heroic nude, the male nude in sport, the male nude in nature, representations of gay love – the more one has a sense that L’Homme nu has spread itself too thin. Nevertheless it offers the chance to see many spectacular works, including Cezanne’s Baigneurs, Schiele’s Autoportrait nu, Reni’s Saint Sébastien martyr dans un paysage, and some less frequently seen paintings such as Géricault’s Étude d’un homme, Pallière’s Ulysse et Télémaque massacrant les prétendants de Pénélope, and David’s Académie d’homme, dit Patrocle.

The exhibition at the Wallace Collection is an altogether more focused and learned affair with its exposition of a mere thirty-seven carefully chosen drawings from the extensive collection belonging to the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Its more precise and descriptive subtitle is ‘Eighteenth-Century Drawings from the Paris Academy.’

Rather than offering an alternative history of Western art by displaying depictions of the male body instead of the female body, The Male Nude reminds today’s spectators of what used to be one of the most esteemed and institutional forms of art. The male human figure formed the basis for painting and sculpture for well over two centuries at the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris. Founded in 1648, the Académie was one of France’s oldest institutions and eventually evolved into today’s École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts.

The young artist was usually apprenticed to an established painter, and often spent time training in Rome, but also attended the Académie. Mastering the techniques of representing the male nude in drawing, painting and sculpture was at the core of the Académie’s curriculum. The male figure was so highly regarded, in fact, that at first the art student – who was always male at the Académie – was only allowed to copy the drawings and engravings of established artists, and to make casts of antique sculptures of male figures.

Only after he had accomplished this could he begin to draw a real male nude in the setting of life drawing classes. Mastering male nude drawing allowed the artist to move on to history painting, which was considered to be the highest genre, and which featured episodes and heroic characters from classical history and literature, such as Hercules and Apollo. The aim was not merely to draw the anatomy directly and as it was seen. More important to the seventeenth and early eighteenth-century neo-classical theory of art was the idealization of nature: the artist had to improve on reality and somehow extrapolate its ideal essence.

Drawings of the male nude were so closely associated with the Paris Académie that they came to be known as ‘académies’. The curriculum of London’s Royal Academy of Art, founded in 1768 and modeled on the French Académie, had a similar emphasis on life drawing (a practice that only appears on art college syllabuses as an elective today, if at all).

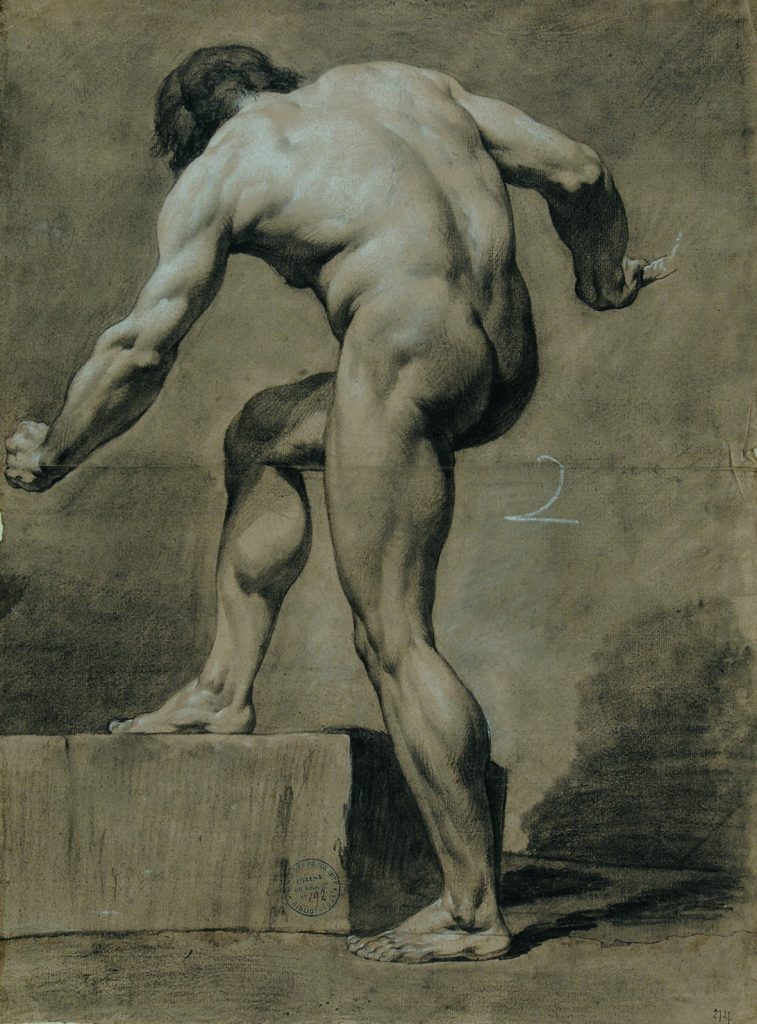

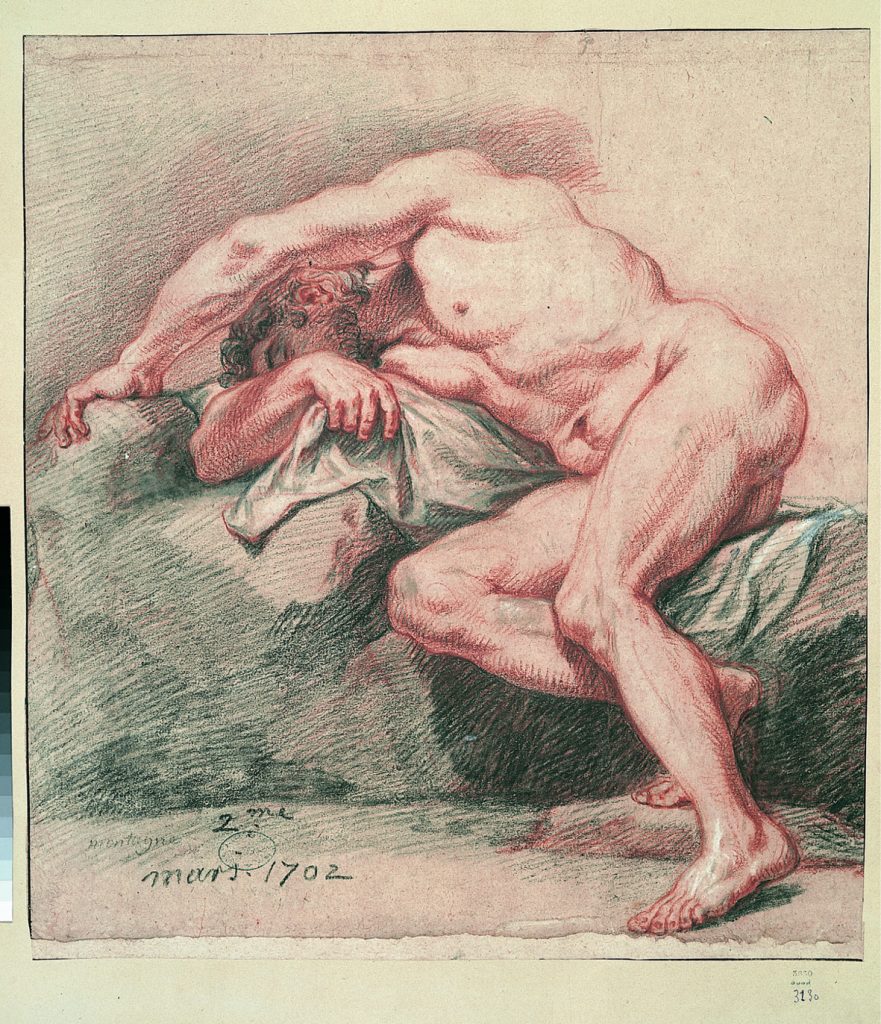

The Male Nude manages to explain some of the technicalities of life drawing classes, as well as displaying some beautiful master drawings by great artists who either studied or taught at the Académie. In the first of its two rooms, for example, we learn about the classroom setting through a series of four drawings, each by different artists, of the same model in a dynamic pose that emphasizes the contours of his muscles and twist of his torso. All four were made at the same life drawing class in 1782 and show how the art students gathered around the model in a circle, each drawing him from a different angle. They also reveal stylistic differences between the various artists.

The drawings illustrate the classroom arrangement not only for students but also for the model, who often had to use ropes and sticks to lean on in order to maintain his tiring pose for the necessary amount of time; these accessories are sometimes included in the drawings. Models were carefully selected. Their bodies had to be clearly defined and representative of the types of figures the artist would most likely depict in history paintings, such as the muscular young hero or the emaciated and sinuous old man. The model was studied for weeks in the life class. Then, the artist was expected to turn what he had learnt into an ideal figure, using his skills to portray a character in a history painting.

Models were never female since ‘respectable’ women would not have posed naked. But there was also consideration of the male art students who – often only sixteen years old – were considered too young to be exposed to the female form. However, this created a problem, since they eventually would have to learn how to draw and paint classical goddesses and nymphs. Ironically, they would end up looking in brothels and disreputable places for female models, who would then have to pose in the privacy of the artist’s studio.

The École des Beaux-Arts has one of the largest collections of old master drawings in the world, second in size and importance only to the Louvre. The thirty-seven drawings in The Male Nude have therefore been chosen for specific reasons. While some are appropriate for introducing the technicalities of the Académie’s life drawing class, many are master works by artists whose paintings also feature prominently in the permanent Wallace Collection. The latter has one of the best collections of eighteenth and nineteenth-century French paintings outside France, but few drawings. This exhibition therefore complements the existing collection while simultaneously revealing from where these painters emerge in terms of training and education.

There are some particularly fine drawings by François Boucher, Carl van Loo, Jean-Baptiste Isabey, and François-Guillaume Ménageot. Earlier works include Charles de la Fosse’s 1678 Orestes pursued by the Furies and Antoine Coypel’s 1687 Man lying on his back, ankles crossed. Black, white and red chalk were used for Académie drawings, but the effects vary greatly and can be colourful, particularly on varying shades of beige, blue and brown paper.

In the exhibition catalogue, clear and absorbing essays by Georges Brunel, Emmanuelle Brugerolles and Camille Debrabant explain the changing tendencies and styles in life drawing at the Académie throughout its history, which were both influenced by particular teachers and representative of general tendencies in art during different periods. Wallace Collection director, Christoph Vogtherr, together with École des Beaux-Arts director, Nicolas Bourriaud, have overseen a gem of an exhibition which complements the Wallace’s permanent collection, and introduces the general public both to the École des Beaux-Art’s prodigious holdings and to the half-forgotten form of academy drawing that was the basis of training for painters for two and a half centuries.

This article was published in The London Magazine.