Intelligent, unpredictable, occasionally ruthless, Jumblatt shows that he is still very much in the game.

The hills along the coastal road south from Beirut are blemished by ugly highrises and concrete blocks abandoned mid-construction, so as I negotiate the lawlessness of the highway, I prefer to glance at the banana plantations and the blindingly blue sea to my right. On this particular morning, the heat and humidity filled the car despite the air conditioning, and my dress was already creased. As soon as I turned off the coastal road at Damour, I began the climb into the Chouf mountains.

The heat became increasingly dry and the air cleaner as I circled green mountains and pine valleys. Most of the villages along the way are modest but others are clearly prosperous. Deir el Qamar, for example, the seat of local governors from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, is beautifully restored. It was Prince Fakhreddine II of Mount Lebanon who first moved his capital here and grew so powerful that the Ottoman sultan eventually had him killed. Although now in the heartland of the Druze community, historically it had a mixed population of Christians, Muslims and Jews.

Deir el Qamar could stand as a microcosm of the country, with its eighteen different religious sects, many of which have coexisted for centuries. The Chouf has traditionally been inhabited by Druze and Christians, who retreated into this mountainous region for self-protection long ago. The Druze are perhaps the most intriguing of the religious minorities in Lebanon, both because of their closely-guarded spiritual beliefs, which are accessible only to the initiated, and thanks to their long-standing reputation of being close-knit and fierce fighters. Walid Jumblatt, the current Druze leader and head of the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP), consolidated his power in the Chouf during the 1975-90 civil war and has made his main home here. One of the most politically canny and charismatic politicians in Lebanon today, he represents a fascinating form of feudalism that persists in a modern, democratic country. I was on my way to see him after his recent controversial announcement that he had withdrawn from the pro-West ‘March 14’ governmental alliance.

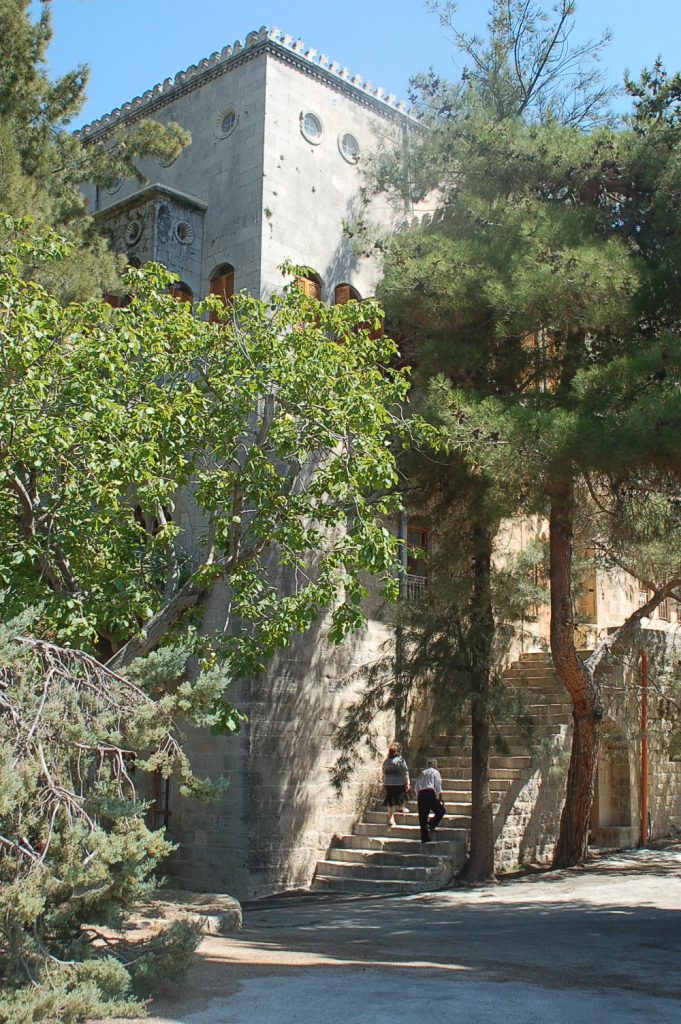

Rounding the head of the Chouf’s main valley, I passed Beiteddine, Lebanon’s most magnificent palace built by local Prince Bashir II, and a little further up the mountain, I came at last to Moukhtara, the home of Lebanon’s Druze leader. I couldn’t see much from the road, but the entrance to my destination was recognizable by the crowds of cars and people. After parking the car, a muscular guard holding a Kalashnikov let me by with an unexpectedly friendly greeting. Ushered through the gates and security check, I continued up the incline until I found myself at the foot of a towering nineteenth-century palace.

Climbing the old stone stairs to one of the main gates, I became increasingly aware of the palace’s architectural beauty and the stunning mountain views it offered. Parked at the bottom of an elegant double stairway leading to another entrance, probably the residential quarter, was a silver and black Harley Davidson: a sleek, modern machine gleaming brightly in this historical and mountainous haven.

In the main courtyard of the faultlessly restored chateau, locals, visitors and semi-official men stood about. Entering through the first doorway, I emerged into an informal majlis or sitting room, where, surrounded by men and visiting supplicants, I found my host. Tall and skinny, with his extraordinary trademark hairstyle, and wearing jeans and navy blazer, he looked and carried himself more like a Sorbonne professor than a warlord.

At Moukhtara, Walid Jumblatt regularly holds court, opening the doors of his palace to members of his community who come to discuss problems and ask for favours. Jumblatt has been called many things: Lebanon’s political weather vane whose manoeuvering reveals the current state of local, regional or international politics; a well-read figure whose quasi-philosophical political statements inspire flurries of media speculation; a cunning practitioner of realpolitik whose shifting allegiances ensured his survival and the protection of the minority Druze community throughout the Lebanese civil war and since. He is probably all these. But for me, his role as a modern feudal lord explains a lot about his politics.

With his sharp eye, he quickly spotted me and interrupted his consultations to greet and lead me into an anteroom before his private study. Here, pre-colonial maps of the Middle East hang on the walls, alongside a large, framed photograph of his father Kamal Jumblatt, one of the defining figures of twentieth-century Middle Eastern politics. An intellectual politician who studied extensively in Beirut and at the Sorbonne, Jumblatt Senior founded the PSP in 1949, led a major uprising in 1958, united the leftist parties with a secularist, pan-Arab ideology, and supported the Palestinian nationalist movement. In 1977 he was assassinated – like his own father before him.

Only two days after I had first spoken to Walid Jumblatt on the telephone, he had declared his withdrawal from the March 14 bloc, a sudden move that arguably spelled its demise, and had spent the previous several days fielding criticism for this move. The March 14 bloc is a Sunni, Christian and Druze alliance that arose after the assassination of the late Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, who was responsible for most of Lebanon’s reconstruction since the 1975-91 civil war. The assassination led nearly a quarter of the Lebanese population into the streets on March 14 2005, in the largest peaceful demonstration the country had ever seen. The people demanded an investigation into Hariri’s death and the departure of Syria’s military presence from Lebanon. Washington neo-cons seized on this genuinely hope-filled ‘Cedar Revolution’, and Damascus was pressured into withdrawing its troops, which had been present in Lebanon since 1976. Jumblatt was at the forefront of the movement.

Hezbollah, which represents the majority of the Shi’a population and is supported by Syria and Iran, together with its Christian allies led by Michel Aoun, became the official Opposition to the pro-West March 14 government bloc. The neo-cons, unsurprisingly, proved themselves to be treacherous allies when they gave Israel the green light to bomb Lebanon in July 2006, hoping to get rid of Hezbollah once and for all. But the near-continuous bombing that lasted 34 days led to the destruction of the country’s infrastructure (airport, roads, bridges, power station), environmental disasters and over a thousand civilian deaths. Hezbollah, meanwhile, only gained more supporters, mostly from among the Shi’a population who were most affected by the bombing.

Many admit that the March 14 government was disappointing. The Hezbollah-Israel war revealed its weakness. At the end of 2006, after a Shi’a cabinet walk-out over the Hariri tribunal, it was unable to appoint a president for eighteen months. The government’s limitations were again exposed when it tried to dismantle the Oppositions’ telecommunications network, triggering an attempted coup. Syria’s withdrawal had little impact on the everyday workings of Lebanese politics, however, which remained riddled by sectarian antagonisms, corruption and partisan allegiances to outside powers.

Despite differences of opinion on a number of issues within the March 14 bloc, Jumblatt’s announcement was nevertheless a shock. At Moukhtara, I suggested to him that he had dealt the alliance a fatal blow. His answer was succinct: ‘The demands of 14 March are accomplished. We have the mandate for the withdrawal of the Syrians and the Syrians got out. We’ve asked for a tribunal, we’ve got a tribunal. What else? Independence, liberty, freedom… And then what?’

I pressed him on the timing of his withdrawal – only two months after March 14 won the election. He cited the need for the protection by a greater Arab community, speaking of ‘good relations with Syria’ and ‘our cousins and relatives in Syria’, and emphasizing an Arab identity: ‘I feel much more secure when I stick to my Arabness. I am Druze but without Arabism there is no protection.’

This was a 180-degree turn from the man who had spoken out so daringly against Syria, and who had publically stated his fear that he might be assassinated – an understandable fear given his father’s fate and the contemporary wave of assassinations of prominent figures who had criticized Syria.

Of course, in earlier years and during much of the civil war, Jumblatt was Syria’s ally. And now, the Bush administration has gone and a thaw is taking place between Syria and the US. Jumblatt is at heart a pragmatist and seems to be responding to wider international changes as well as to local shifts. But he affirmed only that his main concern was how to solve ‘the biggest problem and injustice in the twentieth and twenty-first century, which is Palestine’. He reiterated his pro-Palestinian position and reclaimed his Arab identity, brushing off his previous stance as a mistake: ‘At one time I committed the error of going to the neo-conservatives […] Now I’m back to my origins, hamdulilah (thank God).’

It’s hard to trust the sincerity of this return to his leftist roots or, for that matter, of his earlier flirtation with the neo-cons. I put it to him that during his time as a March 14 leader, he had let down the Druze of Syria, who, as a vulnerable minority, may have been endangered by his provocative statements against Syria. He did not attempt to justify himself and, with a sigh, simply admitted that he had.

Perhaps sincerity is irrelevant for any Lebanese politician, let alone one as slippery as Jumblatt, since history so often seems to repeat itself in Lebanon: Israeli invasions, Syrian interventions, regional and international attempts to influence local actors, and a confessional political system that sees sons succeed fathers as leaders of the same, slightly updated political parties. Time curiously stands still in the midst of apparently dramatic changes, and it is perhaps Jumblatt’s philosophical bent, combined with the unflinching loyalty he receives from his community that make him a continued and potent actor on the political scene. In reality, many Druze were quietly horrified at his withdrawal from March 14, but the fact that they continued to support him ensured his lasting power and, in turn, their own protection.

Jumblatt certainly enjoys an idiosyncratically strong loyalty from his community. He is known as Walid ‘Beyk’, a title (originally military) conferred on the Jumblatts centuries ago. Among the people surrounding Jumblatt in Moukhtara during my visit, there was a woman with a baby in her arms, a foreign woman and her Lebanese husband, and several men waiting patiently to gain the leader’s ear. The supplicants come to ask for help with legal issues or land conflicts with neighbours, or to make requests on behalf of their children, who may need a scholarship or help in becoming officers in the army.

They sit or stand informally, but respectfully, in the reception room, where cushion-covered seating runs along all four walls, and in the outer courtyard, where they can lean against a traditional well or under an ancient Byzantine mosaic on the wall. The semi-official men who seemed to hang about aimlessly, talking in low tones, are modern ‘courtiers’ in charge of the various Druze educational and social institutions, so that particular requests may be followed up immediately. Most were wearing casual suits and shirts without ties, but a few had on the traditional Druze sherwal (baggy black trousers) and white skullcap.

Not all those who make the trip to Moukhtara are Druze, since there are many Christians and some Sunni and Shi’a Muslims who live among Druze communities and whose interests are also partly represented by Jumblatt. Full of nervous energy, the Beyk doesn’t sit still for very long and is given to checking his mobile phone while people whisper their requests. He makes impatient noises or raises his voice when someone comes along with a banal problem, such as a collapsed garden wall. A white hunting dog dozes by his side throughout these consultations and then follows him from room to room.

This cosy feudalism initially seems at odds with Jumblatt’s pragmatic politics, but it is even more strange when one considers his modern, cosmopolitan outlook. For instance, he founded the annual international Beiteddine music festival during the civil war, and his wife Noura is a keen patron of the arts. A wine enthusiast, he is the majority shareholder in Chateau Kefraya, Lebanon’s second largest winery, and he adores Harley Davidsons. He is also said to enjoy a party. Most significantly, as president of the Chouf Cedar Reserve committee, Jumblatt has helped save the Lebanese cedar tree and countless endangered animal and plant species, and has created the largest nature reserve in the country. His concern for the environment has spread throughout the area: on my drive up to Moukhtara, I was struck by the spotlessness of the landscape. There is no litter here as there is all along the coastal road, and the detritus of building developments that seem to be ubiquitous in the country are a distant memory.

And yet, the feudalism is not really so odd. It is a logical extension of the Lebanese confessional system that distributes political positions according to sect and therefore permits the persistence of a traditional feudalism in the modern form of political clientelism. The Prime Minister must be Sunni, the President a Maronite Christian, the Speaker of the House a Shi’a Muslim, and so on, more or less, among the eighteen official sects.

Druzism is a philosophical offshoot of Shi’a Islam (Ismailism, to be precise) and is influenced by Sufism. Its esoteric nature kept it secret from all but the initiated, partly for the protection of the community. I asked Sami Makarem, professor of Arabic Literature, Islamic Thought and Sufism at the American University of Beirut, to explain the strong feudal allegiance the Druze continue to offer their leader. For Makarem, the Druze are historically a military people: they descend from the Tanukhids, who came from the Aleppo region to Lebanon in 1017 because the Abbasid authority wanted them to defend the Lebanese coast from the Byzantines. The Tanukhids embraced Ismaili Shi’ism and then Druzism, and continued to defend the Lebanese coast and Beqaa valley for the following five centuries under the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk dynasties. Their military past explains the way in which their leader became both a military and a political figure. The importance of land accompanies this type of military loyalty, particularly as the Druze were granted feudal fiefdoms by the caliphates and local empires they defended. Interestingly, the Druze are today the only Arabs allowed to join the Israeli army, part of Israel’s ‘divide and rule’ policy over the Palestinian population. But in most of the region, the Druze have been strongly associated with anti-colonialism and nationalism.

Jumblatt’s current political about-turns may be viewed cynically, but they are effective because of his community’s support, and the return to his leftist roots is not so much ideological as simply a question of security and self-protection. ‘I feel safer as part of a bigger group’, he says. He believes that there used to be ‘a more effective left’ in the Middle East during his father’s era, but that now, in the age of globalization, there is no alternative but to be pragmatic.

So what is Jumblatt confronting now? His own explanation that March 14 achieved what it had set out to do is certainly true. The alliance did not, as was hoped, lead to a more profound unification of the nation. There remained differences in opinion among the allies, and the division between March 14 and the opposition was further cemented. This was apparent even after March 14’s election victory when it took months to form a cabinet. Jumblatt has local concerns, to be sure, including jockeying for important cabinet seats and achieving neutrality in any potential Sunni-Shi’a rift within Lebanon. But his manoeuvering is also a response to the wider regional and international situation, which he was the first to understand. With the withdrawal of troops from Iraq and the stated intention to prevent further Israeli settlements in the occupied territories, the Obama administration at least appears to have a different approach towards the Middle East. It is also bringing Syria into the international fold, loosening her strategic alliance with Iran. Recent meetings between Saudi king Abdullah and Syrian president Assad signal a healing of their rift and a possible regional configuration that sees a Saudi-Syria understanding to counterbalance Iran. Jumblatt, in response, is reconfiguring his own position in order to ensure his survival in the new world order.

For Jumblatt, ‘there is no Lebanese nation’: for as long as the ‘old-fashioned, outdated’ sectarian system remains in place, he believes, people will function in a sectarian and feudal fashion. So, for the time being, he can only be pragmatic, remain at the head of his community, and attend to situations as they arise. It is a grim worldview, but one that is at least more plausible than either the overblown rhetoric of the religious parties or the wishful idea that Lebanon can rely on the West to sort things out. Intelligent, unpredictable, occasionally ruthless, Jumblatt shows that he is still very much in the game.

He also continues to maintain a balancing act. While contending to be a player in national politics, he must simultaneously represent the Druze community effectively enough to preserve his position as their leader, and also respond to the politics of external powers who are always nearby and ready to meddle in a small, weak Lebanon. Although many condemned his abandonment of March 14, many others, certain at least of his survival instinct, wondered what he knew or foresaw that they didn’t.

Read the full article in Granta here