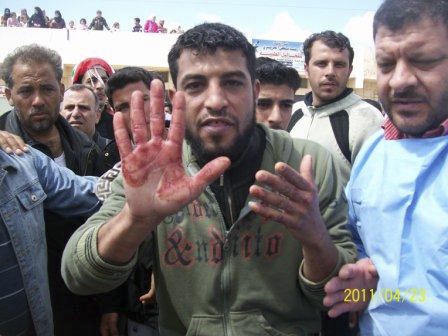

Over Easter weekend, the government of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad launched a brutal crackdown on the peaceful protests that have been gathering force across the country in the last five weeks.

Over Easter weekend, the government of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad launched a brutal crackdown on the peaceful protests that have been gathering force across the country in the last five weeks. Around 120 protesters were killed in several different cities by security forces (bringing the total to some 400 since the protests began); and thousands more were arrested. On April 25, tanks moved to Daraa, the southern city where the protests first began in mid-March, triggered by the arrest and torture of teenagers who had scrawled anti-government graffiti on the city’s walls. Near Damascus, the towns of Douma and Moadamiyeh have been similarly sealed off, as have Baniyas, Homs, Jableh, and Hama, and people I am in contact with tell me that there are soldiers on every street corner in the northwestern port city of Latakia.

In areas where protests have occurred, hospitals were ordered not to treat activists—and some doctors who disobeyed have been arrested. I have also received news that injured protesters are being taken away by police from their hospital beds.

As this fierce response unfolds, checkpoints in protest areas have been set up to search people for mobile phone pictures and footage of the violence. Telephone and Internet networks in Daraa and Douma have been cut, and few people have been able to leave or contact the outside world. There are reports of government snipers firing on pedestrians, and residents no longer dare leave their homes. Rooftop water tanks have also been targeted by snipers in Daraa, where electricity has also been cut off. Foreign journalists, who in recent weeks have been harassed and dissuaded from pursuing their stories (and in a few cases arrested and beaten), have now been expelled.

The dearth of information has raised questions about who is involved in the protests, the breadth of popular support for them, and what prospects they might have—in the face of such repression—to bring about a broader change. While it has been increasingly difficult to get a full picture of the towns and cities where the government has responded with force, some insights can be gained from the situation in Douma, a flash point in the protests, which I was able to visit shortly before the most recent violence.

Often called a suburb of Damascus, Douma is a mostly lower-middle-class town of about 112,000 people struggling with unemployment. There are some doctors, lawyers, and professionals, and students who commute to Damascus University, but most residents are workers and lower-ranking government employees. Those who don’t use the Internet have at least some friends or relations who do, and certainly have access to mobile phones. The younger generation is, of course, more technologically savvy; many know how to keep in touch with people in and outside Syria, and therefore have taken the lead in the protests. Demonstrations began early on in Douma, both in solidarity with the people of Daraa, and because its residents had similar grievances against the Syrian government’s political corruption and oppressive security state.

Read full article in the New York Review of Books here