In 1862, over half a century before the fall of the Ottoman Empire and before the British and French carved up the Middle East, the then Prince of Wales went on a four-month tour of the region.

The future Edward VII visited Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey and Greece, on a tour that was arranged by his parents, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, to keep him busy between university and marriage. Although Prince Albert died in 1861, Queen Victoria insisted that Prince Edward’s journey would go ahead.

The royals were enthusiastic supporters of the recently-invented medium of photography, with its realistic depiction of the world, and they had the brilliant idea of sending along the photographer Francis Bedford to record the trip.

On the prince’s return, 172 of Bedford’s photographs were exhibited to the public in London and then published in a book. They were a great success, giving Britons the opportunity to see realistic images of far-away places.

“Cairo to Constantinople: Early Photographs of the Middle East” at the Queens Gallery in London assembles these photographs again for a contemporary audience.

Today’s audience, however, is both constantly exposed to visual images and attuned to the pitfalls of Orientalist representations which objectify and distance foreign peoples – particularly those who would soon be colonised. It may be surprising, then, to find that these images are utterly compelling – not only for their obvious historical importance, but also because of their quality and sheer beauty.

The photographs

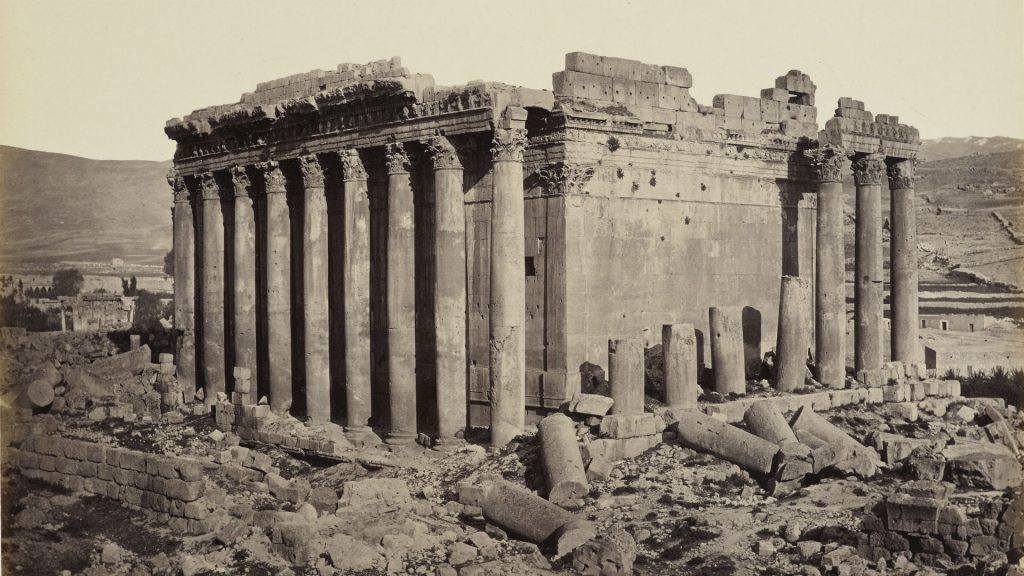

With only a portable tent to prepare the photographic plates and work on them after they were exposed in the camera, Bedford nevertheless produced some stunning images.

They have a sharpness and clarity that is absent in contemporary digital photography, and they capture the awesome scale and majesty of famous sites, such as the monuments at Luxor, the great mosque of Constantinople and Baalbek temple. A modern audience may be taken aback, though, to see the dilapidated state of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, which underwent renovation years later, under the French mandate and after Syrian independence.

The landscapes – of the desert, mountains or sea – are beautifully composed, and of course they are clear of modern clutter such as road signs, highrise buildings and traffic.

Bedford also presents some haunting images of destruction in the towns of Hasbaya and Rashaya in southern Lebanon and in the Christian quarter of Damascus following the massacres of the Druze-Christian conflict in 1860. The royal tour took place only two years after this conflict, and the ghostly images of destruction are disturbingly reminiscent of today’s pictures of war-devastated parts of Syria, Iraq and Gaza.

Only 21 years old, the prince and his party travelled relatively simply, camping and riding camels when visiting sites, though he also met politicians, monarchs and intellectuals. There are a few photographs of his party, looking politely dishevelled in crumpled suits and long leather riding boots.

Bedford also photographed groups of people who accompanied or met them on their travels, such as the Bashi-bazouk mercenaries of the Ottoman army, the party’s camp attendants in Beirut and the Albanian water carriers.

Several photographs include local people. Their presence shows off the size and scale of the buildings and monuments beside which they stand, sit or gather to chat. But they also provide the Orientalist perspective of poor and picturesque locals who are part of the landscape and don’t really need to be taken into account.

Some of the Arabs or locals in the photos have been obviously composed, for they would have had to hold their positions for 12 seconds for the camera. But others are more natural, particularly when larger groups of people or camels were involved, and their movements make them gently blurred.

There are a couple of intriguing portraits: Abdel Qadir, for instance, an Algerian scholar living in exile in Damascus who fought for independence and protected Christians during the Druze massacres, and a more humble, unknown man whose dignified bearing is sympathetically portrayed.

Tourism in the nineteenth century

Tourism and travel for leisure was becoming very popular during the Victorian period. Travellers were drawn by the idea of visiting biblical lands and by an interest in antiquities and recent archeological discoveries, a process which began many years earlier with Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt in 1798-1800.

Steamships began to be used for the route to Alexandria, making travel faster and easier for Europeans. By 1867 Thomas Cook & Son had started to arrange package tours to Egypt and Palestine.

As Edward Said and others have shown, political motives often lay beneath cultural interest in the region, and an imperialist ideological perspective permeated it. In the case of the prince’s trip, he was sent to learn about the Middle East at a time when the Ottoman Empire was ailing and Britain already had designs on the region to secure a route to India.

Read the full article here