As the conflict drags on in Syria the tensions are felt strongly in Lebanon, which is hosting almost one million refugees.

Lebanon’s 70th-birthday celebrations on 22 November were overshadowed by fears that national unity and sovereignty were cracking under pressure. This small country is not only feeling the strain of the influx of Syrian refugees – the fastest-growing refugee population in the world, soon to be the largest. It is also being dragged into regional and sectarian tensions that are increasingly played out on its soil, as testified by the twin explosions carried out by al-Qaeda-affiliated suicide bombers against the Iranian embassy in Beirut three days before Independence Day.

There are almost a million Syrian refugees registered in Lebanon. Many others are not registered, and with 3,000 new refugees entering the country daily, unofficial estimates indicate that there will be two million by next year. Lebanon has a population of just over four million, so the strain on its economy, schools and health services is immense.

Lebanese internal conflict over Syria falls along the lines of the main political blocs. Hezbollah, the dominant party and militant Shia group supported by Iran and Syria, has sent fighters into Syria to defend the Alawite regime of President Bashar al-Assad. The pro-west “March 14” alliance – made up of Sunnis and Christians, together with centrists – opposes this involvement. Lebanon has had a caretaker government for the past eight months thanks to widening rifts between the two blocs. The former prime minister Najib Mikati resigned after Hezbollah’s “March 8” alliance opposed his attempt to renew the term of a senior security official. Since then, a stalemate over allocation of cabinet seats has prevented politicians from forming a new government.

Considering the government’s weakness and the historical resentment that many Lebanese feel about Syria’s influence over Lebanon’s politics, their country has been remarkably hospitable towards the refugees. When the Syrians first started arriving in north and east Lebanon, families even in these deprived areas offered them free shelter and food. But social tensions are rising. The presence of the Syrians is increasing competition for jobs, and they are undercutting Lebanese workers because they provide ever cheaper labour.

Even more pressing is the humanitarian crisis. This year has brought the proliferation of “informal tented communities” along the Beqaa Valley, in the area north of Tripoli and in the south. Many lack basic sanitation, weatherproofing, clean water, food, clothes, blankets and fuel for heating. There are also medical shortages; as winter approaches, the consequences could be dire. Ninette Kelley, the resident representative for UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency, has described the situation as a “human catastrophe”.

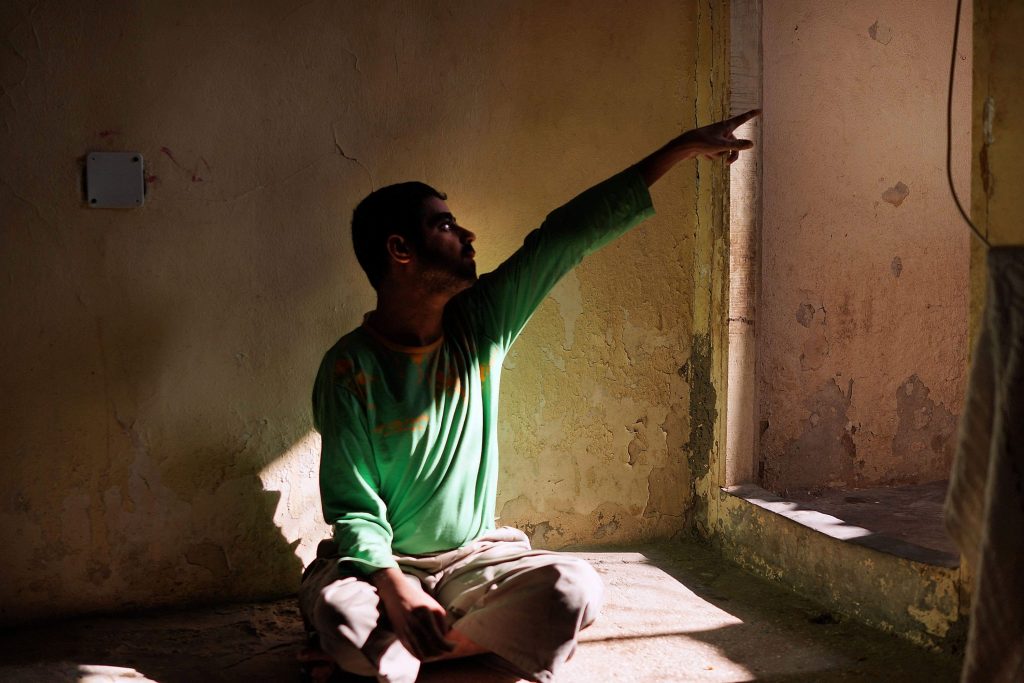

Political considerations initially made the Lebanese government slow to react. Unable to forget the influx of Palestinians fleeing Israel in 1948, and fearing that the predominantly Sunni Syrians would bring about greater demographic and sectarian change, the government prohibited the construction of formal refugee camps or semi-permanent structures. As a result of this policy, Syrian refugees have settled throughout Lebanon rather than in designated areas and organised refugee camps, as is the case with refugees in Jordan and Turkey. They live in terrible conditions in sheds, underground garages and unfinished structures.

Lebanon has been praised for keeping its borders open to Syrian refugees, yet the international community has not offered sufficient assistance. The rich Sunni governments of the Gulf have avoided funding the Lebanese government directly, as a way of punishing it for Hezbollah’s influential role in the state. Instead, they fund local (often religious, Sunni) charities. Some of these could be using the aid to buy arms for training Syrian opposition fighters, or even to carry out attacks inside Lebanon.

Western aid agencies suspicious of corruption have also bypassed the government. But consequently the assistance available is short term. It completely neglects strategies to develop infrastructure in ways that could help Lebanon cope with the refugees and ease tensions between refugee and host communities.

Belatedly, Beirut and the World Bank have come up with a secure trust fund through which to channel aid. Even so, the government must reform its structural weaknesses if it is to gain control of the situation, and it needs international support to do so. The Lebanese don’t want to return to the fragmentation of 1975-90 and the civil war, but on Independence Day this year, a unified Lebanon was more challenged than celebrated, as changes in the population and regional Sunni-Shia tensions threaten a country that relies on sectarian power-sharing.

Read full article here